Few fantasy creatures are as popular as goblins have been in recent years. This is not to say that we suddenly started supporting them while reading The Hobbit; still, they have become a symbol of certain aesthetic and lifestyle trends storming the social media of the pandemic era. We are talking about goblincore, an aesthetic that affirms the chaotic side of nature, and goblin mode, a term that has been announced the word of 2022 according to the Oxford Dictionary.

The term goblincore started to gain popularity in late 2019. It signifies yet another online micro-aesthetic – emerging from a space somewhere between Tumblr, TikTok, Pinterest and Reddit. Like many similar phenomena, goblincore is a certain feeling rather than a crystallised movement; more than that, it can manifest itself in fashion, interior design, graphics and lifestyle alike. It is thus not only an aesthetic niche, but also a potential subculture – if the concept of subculture still makes any sense in the early third decade of the 21st century.

So what characterises goblincore? To cut the long story short: the dream of community with nature. Obviously, this is not the only online micro-aesthetic celebrating the proximity of man and nature; even before that, Tumblr seduced us with cottagecore, a vision of idyllic, peaceful life in the countryside. But whereas cottagecore depicts nature in an idealised way, as a kind of a picturesque backdrop, goblincore is centred on what we perceive as chaotic, dirty and sometimes just plain disgusting. Mushrooms growing from rotting tree trunks, swamps full of squawking frogs, animal bones abandoned in the forest, snails, lichen and mud – it is this face of nature that has become the aesthetic axis of goblincore. From the perspective of this trend, these seemingly unpleasant sights gain a magical dimension, becoming downright appealing, like the thrill of reading a fairy tale.

Goblincore aesthetic – pilled sweaters and skulls on the shelf

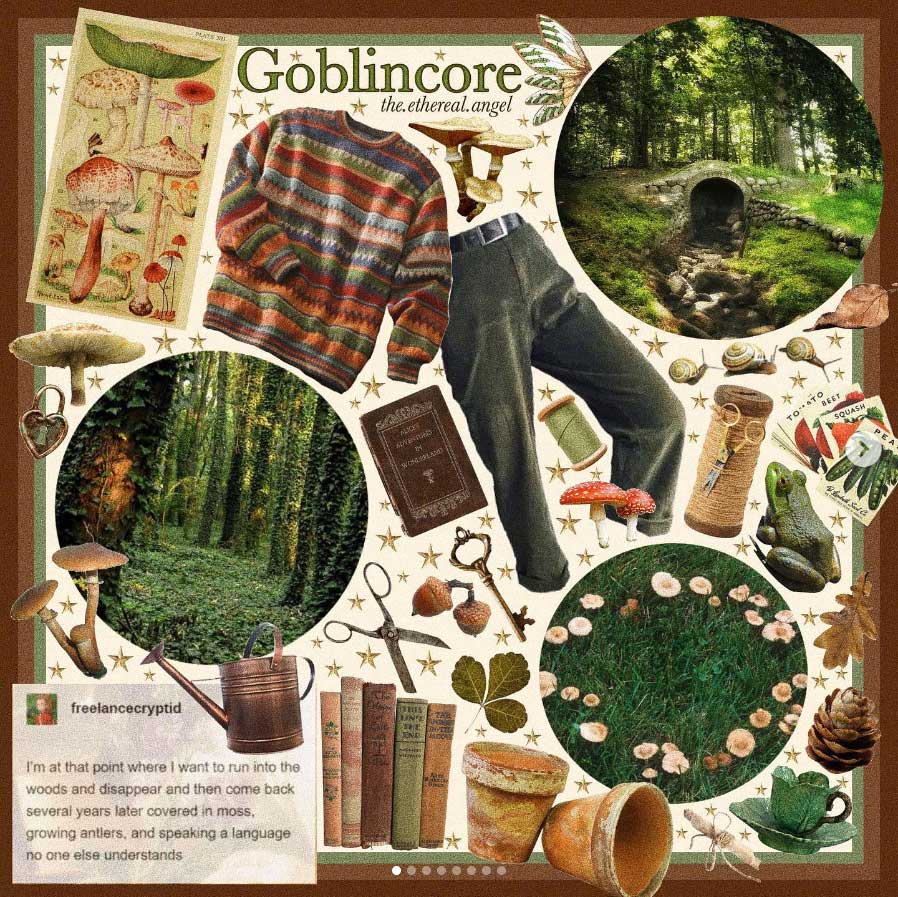

Goblincore can invade our everyday lives in a number of ways, the first and perhaps the most obvious one being fashion. The goblincore approach to clothing is characterised by apparent unkemptness and a programmatic rejection of elegance or even neatness. This is why goblincore outfits often feature stretched, patched and pilled sweaters, flannel shirts, corduroy trousers or skirts, all preferably in a colour palette ranging from shades of brown to rotten green. Importantly, goblincore encourages the purchase of second-hand things, including clothes, thus revealing its anti-consumerist and eco-friendly side. Still, as is often the case with anti-aesthetics, the unkempt appearance is the result of strict selection – after all, it is not about any unkemptness, but about “stylish” and intentional unkemptness.

Goblincore has become an inspiration for manufacturers and brands, particularly, but not exclusively, clothing ones. Many independent makers on Etsy.com describe their goods with this term; on the platform, we can buy not only goblincore clothes, but also goblincore mystery boxes filled with all kinds of trinkets. Goblincore clothing is offered by Cosmique Studio, which specialises in micro-aesthetic products and the same goes for Cottagecore Clothes. Although we still have to wait for a larger promotional campaign in the spirit of goblincore (if you know of any, be sure to let us know! ), the theme of this aesthetic has been picked up by many corporate blogs, not only branding agencies (as in our case), but also photo editing apps, outdoor clothing manufacturers and real estate agencies.

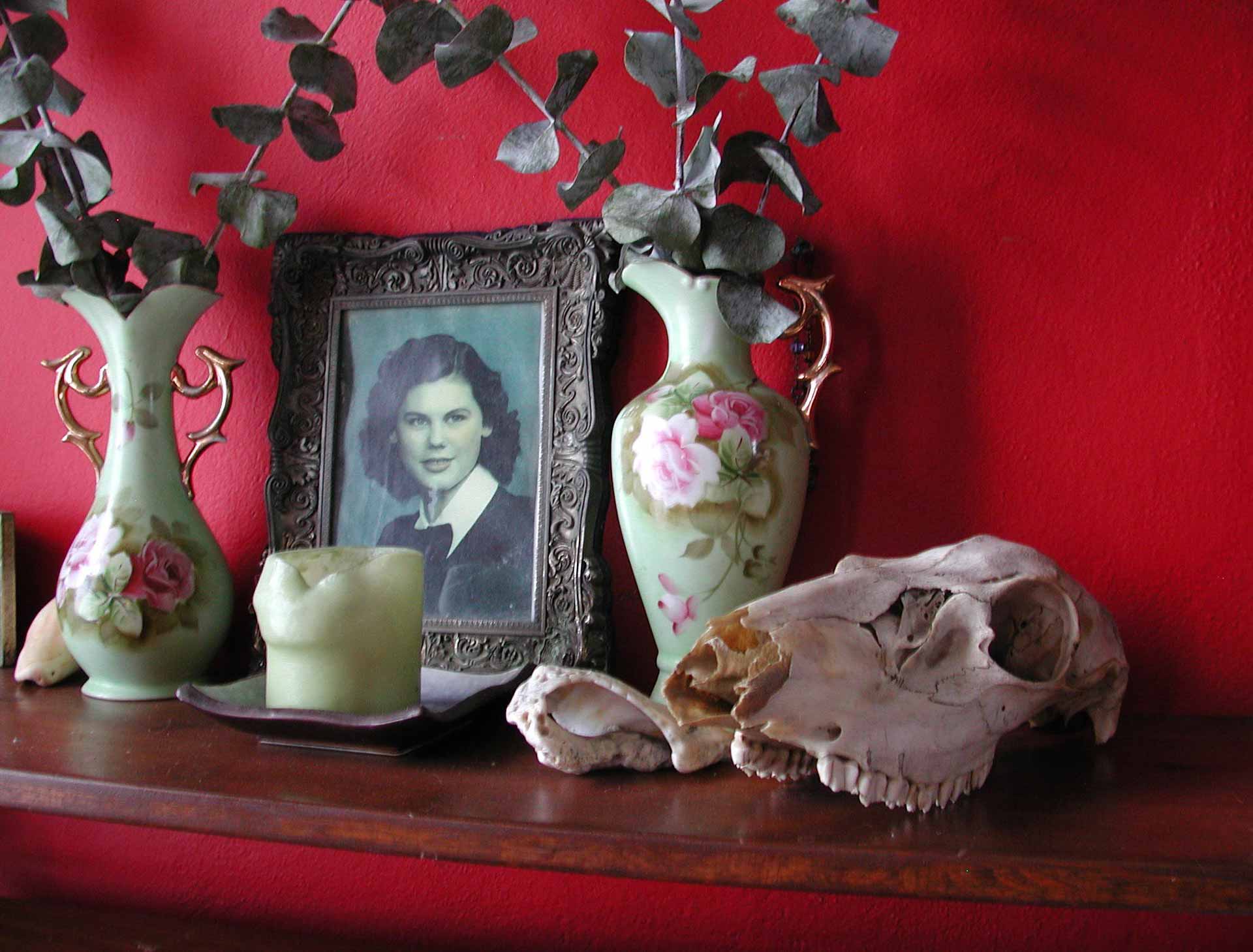

And when it comes to real estate, goblincore is also a style of interior design. Here, too, it is also about a stylish ugliness, best achieved by thrift shopping or simply finding the desired items. Preferably second-hand and old, furniture should reveal the natural texture of the wood. To complement your goblincore interior styling, choose animal skulls found in remote areas, pinecones, shells, dried plants or crystals. Old books, coins, pendants, engravings and photographs will be also fine. Perhaps most importantly: goblincore is an anti-minimalist aesthetic. It seeks to achieve cosiness through excess, so you should not be afraid of displaying the whole collections of the aforementioned items on the shelves or walls. But all these decorations get dusty in no time, don’t they? Well, all the better.

Internet micro-aesthetics attempt to provide holistic ideas about life when it comes not only to clothing and interior design, but also to lifestyle, activities and interests. It is hard to imagine a more goblincore hobby than walking for hours in the scrubland, collecting bones, looking out for elves and sketching the animals and plants one encounters, but obviously not everyone has this opportunity on a daily basis. Antique shopping, reading fantasy novels, experimenting with fermentation or taking part in D&D sessions – as long as we feel like meeting others – seem to be reasonable urban alternatives.

Problems with goblins

Why it is goblins that have become patrons of the new trend rather than much more likeable dwarves, gnomes, fairies or elves? Goblincore does not focus on an idyllic vision of nature. Quite the contrary, it is interested in the wild and exuberant; as for nature, it is viewed as an ecosystem full of insects, funghi and decay. It should come as no surprise, then, that it is the goblins, creatures associated with mischief and boorishness, that have come to symbolise the new trend

Goblins have also become a reference point for what is known as goblin mode, an attitude of rejecting the aesthetic expectations of others, being completely lazy and indulging in on one’s own, often unhealthy, whims. Have you ever spent a weekend without taking a shower, in old tracksuit bottoms, eating nothing but cold pizza and playing console games all day? Great – that’s what goblin mode is all about. The term went viral due to a fake news story attributing its use to actress Julia Fox, in the context of her split from Kanye West. Whatever its origins are yet, goblin mode has made a huge meme career – all the way to being named Word of the Year 2022 by the Oxford Dictionary.

Goblincore and goblin mode seemingly have little in common, apart from their online popularity and the goblins themselves. Yet both phenomena seem to have grown out of the same soil – rejecting he pursuit of aesthetic and social ideals, an attitude stimulated by the pandemic isolation. We do not have to be financially successful, we do not have to be socialites, we do not have to succumb to the dictate of the gaze of others – this is what both goblincore and goblin mode tell us. Instead, you can cherish your own eccentricity and imperfection, which is fully sufficient to be satisfied with your life, spending your days loitering in forests and meadows or around your own flat, if you wish so.

Although the unfriendly, self-centred and solitary goblin has become, perhaps surprisingly, a positive archetype in its own way, we cannot stay silent about the related problems and controversies. Some representations of goblins, whether related to their appearance (curved noses) or their behaviour (greed, hoarding of “trinkets”), are sometimes interpreted as reminiscent of the worst propaganda models of anti-Semitic parody. It is this portrayal of goblins that is one of the reasons for the heated criticism of both the Harry Potter series and Hogwart’s Legacy, a video game set in the same universe. Goblincore has developed two tactics to protect this very inclusive trend, especially when it comes to its attitude towards LGBT+ people, against such associations. The first one is the change of name, which is why some people replace the term goblincore with crowcore or dragoncore, or even cottagegoth. The second one is to point out that folklore-derived creature names can have different designations and carry contradictory associations; hence the fairy- and elf-related goblin need not be equated with any cruel caricature.

Goblincore aesthetic – sources, inspirations and neighbouring lands

Goblincore aesthetic has not emerged in a cultural vacuum. Leaving aside the pandemic and isolation, which may have made us, on the one hand, yearn for nature in all its splendour and, on the other, get accustomed to not having to look neat at all – the trend is inspired by or corresponds to a number of other aesthetics as well as social transformations. Let’s take a look at some of them.

Perhaps goblincore could not have existed but for the earlier absolute triumph of geek culture. Fantasy in the broadest sense, or even speculative fiction, has become one of the most important areas of pop culture over the last decade or so; it has ceased to be somewhat looked down upon or seen as frivolous and infantile, becoming a major focal point for the contemporary imagination. Let’s take, for example, RPG sessions – no longer a bizarre, incomprehensible and downright suspicious hobby, but a daily reality in many corporate office rooms after hours. What seemed marginal not so long ago is now mainstream culture. Goblincore is riding on the wave of fantasy – not only by referencing it in its name, but also by being obsessed with the mysterious, the ambiguous and the slightly dark.

You can read and dream about magic, but you can also perceive it as a genuinely causal force. Goblincore perfectly complements the renaissance of (pop)esotericism that we have been seeing in social media for some time. Goblincore interiors are reminiscent of the imagined offices of fortune tellers or even witches’ cottages; crystals and animal bones can equally serve a decorative function or be essential elements of rituals. Goblincore as such does not propose any particular spiritual or occult path. By no means is it necessarily associated with the practice of esotericism, but we can undoubtedly consider it as the “official” aesthetic of WitchTok.

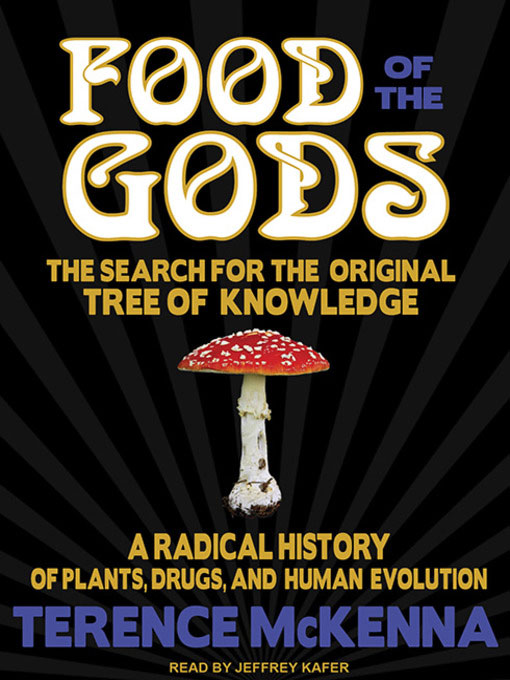

Delving into the mysterious dimensions of reality and establishing a profound bond with nature does not necessarily require any magical rituals; some have chosen to rely on chemistry. The iconosphere of goblincore, in particular the obsession with mushrooms and toads, evokes associations with psychedelic culture, dating back to the origins of prehistoric man, exploding in its contemporary form in the late 1960s and early 1970s and still present in various forms today. If we take seriously the possibility that goblincore is not only an aesthetic but also a subculture, then its character is distinctly neo-hippie.

Goblincore is also entangled in a complex web of various micro-aesthetics, both those that have grown out of the Internet of recent years and older ones. Goblincore represents at least an alternative, if not an antithesis, to the aforementioned cottagecore – a darker and more eccentric one. Somewhere close to goblincore is the micro-aesthetics of green academia. The boundary between the two is quite arbitrary and the only major ideological difference is the latter’s focus on the scientific study of nature. The interest in the darker side of nature (and goblins, of course), in turn, is the point of commonality between goblincore and dungeon synth – a genre of slightly unsettling electronic music, dating back to the 1990s, which is experiencing a renaissance now. The list of similar terms could be much longer; contemporary culture is obsessed with dividing niches into ever smaller, even more specific niches.

A bond with your inner goblin

Like many other online micro-aesthetics, goblincore aesthetic can be accused of superficiality. Is this trend really about any kind of bond with nature and self-expression? Or is it just an ephemeral buzzword leading to nothing but the market exploitation of a pre-existing but still unnamed niche? No matter how strongly anti-consumerist the assumptions of a given aesthetic trend appear to be, its name always ends up as an element of the descriptions of items offered on clothing sales platforms. Besides: is a new aesthetic really created every time we add “core” to any noun? Even with all these doubts, goblincore should not be disregarded and seen as a meaningless concept; its popularity can be analysed in interesting cultural contexts.

First: goblincore is a very nostalgic, even retromantic trend, its iconosphere referring not only to nature, but also to an idealised, imagined past: from folk folklore to grunge. This programmatic rejection of modernity and contemporary technology is paradoxical in its own way; the trend that pretends computers don’t exist came into existence online. However, if we do not focus too much on the irony of this fact, we can see that the essence of goblincore lies in a great longing – perhaps for an irretrievably lost childhood and looking out for frogs in the pond, perhaps for a simpler life in a more magical world that is still possible.

Second: goblincore is part of a long tradition of emancipatory currents and trends. Do we really need to “look decent”? Is spending half the day looking at insects in the grass a waste of time? And why is it not the done thing for adults to collect colourful trinkets? Goblincore challenges conservative notions of what is “appropriate”; while it focuses on one strictly defined type of defiance among a vast array of its possible types, it is ultimately a celebration of the freedom to be weird. Everyone (if not constantly, then at least every so often) can give expression to his or her inner goblin, which not only is nothing undesirable, but actually makes us more interesting people.

Third, looking beyond the (blurred) boundaries of goblincore aesthetic: the Internet obsession with singling out, naming and classifying niches is indicative of a growing aesthetic awareness and sensitivity to subtle differences in design, clothing style or the atmosphere of cultural works. At a time when AI is frighteningly good at generating graphics that maintain the desired atmosphere, we are paying more and more attention to the formal side of culture and are looking for terms that can capture different moods, modes of imagery or feelings.

Goblincore is unlikely to go down in the history of pop culture and aesthetics as an influential phenomenon in its own right. It is not a particularly innovative trend, but rather a repetition of certain ideas that we have seen many times over the decades. Still, aesthetic repetitions should not be ignored because they clearly reveal we are missing here and now.

See also our articles on: cyberpunk aesthetic and 80s nostalgia.