Chornobyl: the branding of disappearance

Share this article

I was preparing to talk to Oleksandra Doroguntsova, the first woman to become creative director at Banda, a leading Ukrainian creative agency and one of the most interesting in Europe. I knew we would talk about a disaster that happened almost 40 years ago. But I quickly realised it would also be a story about a disaster that happened almost yesterday and is still unfolding – a war started by Putin’s Russia.

In the mid-1980s, rumours (from sources such as Radio Free Europe) began to spread in Poland, causing disbelief. Adults, including my parents, were entirely at a loss as to what to do with this information. The news barely reaching us from the West spoke of an accident or explosion at a nuclear power plant in the Soviet Union. Someone knew someone who knew someone whose aunt worked at an institute with equipment to measure radioactivity. And this aunt said there had been an explosion, or perhaps denied it – depending on who passed on this “100% confirmed” information.

Source: Unsplash

Source: UnsplashA few days later, when it became impossible to hide the truth, Polish authorities confirmed the accident at Chornobyl and organized the distribution of so-called Lugol’s solution. It was primarily meant for children. I’m not sure if it helped, but our entire class obediently marched to the health clinic to drink the vile-tasting suspension.

Oleksandra was three years old at the time and lived in Kyiv. She only remembers boarding a plane with her mother to flee to Moscow, where their only relatives lived. “What irony. I think we were able to escape because my grandfather was an official. That’s probably why we got the news early. Being a mother of a four-year-old girl now, I can feel my mother’s fear when she had to flee, not knowing if we would ever come back.”

It was 1986. And so, Chornobyl became a “black legend,” yet another proof that the Soviet Union couldn’t succeed. For me, and probably not only for me, it became a symbol of brutal tragedy and unimaginable losses for people and the environment caused by chronic system failure. It was a warning, showing how a single human error could lead to enormous and irreversible consequences.

Source: Banda Agency

Source: Banda AgencyYears later, it turned out that Pripyat’s radioactivity could also radiate in a very different, this time inspiring, way.

Three decades after these events, HBO’s gripping 2019 series, which tells the story of the disaster and the people involved in the rescue efforts, has captivated audiences. Emily Watson and Stellan Skarsgård, who previously starred together in Lars von Trier’s “Breaking the Waves”, played a duo of superheroes without superpowers who tried to prevent an even greater tragedy. Acknowledging the production’s excellence, Oleksandra remembers the series as something truly painful, something that “makes you feel so weak and small that you never want to watch it again”.

Source: Banda Agency

Source: Banda AgencyIt’s easy to see the impact this production had on the local government, which oversees the remains of the power station. They realised it was the perfect moment to show the world this real, actual Chornobyl and what it looks like today. That’s why Banda took on the breakneck task of designing the branding for this region!

The project began with a site visit. Despite living nearby, most of the Banda team had never set foot in Chornobyl. As Oleksandra recalls, she has been afraid of this place since childhood. She associated it, above all, with fear and having to flee in 1986. ‘Just like today, my family has to flee from the war that Russia started,’ she says.

The trip to the Exclusion Zone proved to be a powerful experience for the designers. All were deeply moved by Chornobyl, its appearance and the emotions it evoked. “We felt it was a portal to the past, where it all happened, but also to the future, where we could all end up if we forget how catastrophic human error can be,” recalls Oleksandra.

Source: Banda Agency

Banda also met with the authorities, who were interested in why the most creative branding agency in Ukraine decided to visit Chornobyl. At the time, the Ministry of Tourism and Environmental Protection and Natural Resources of Ukraine decided on the project.

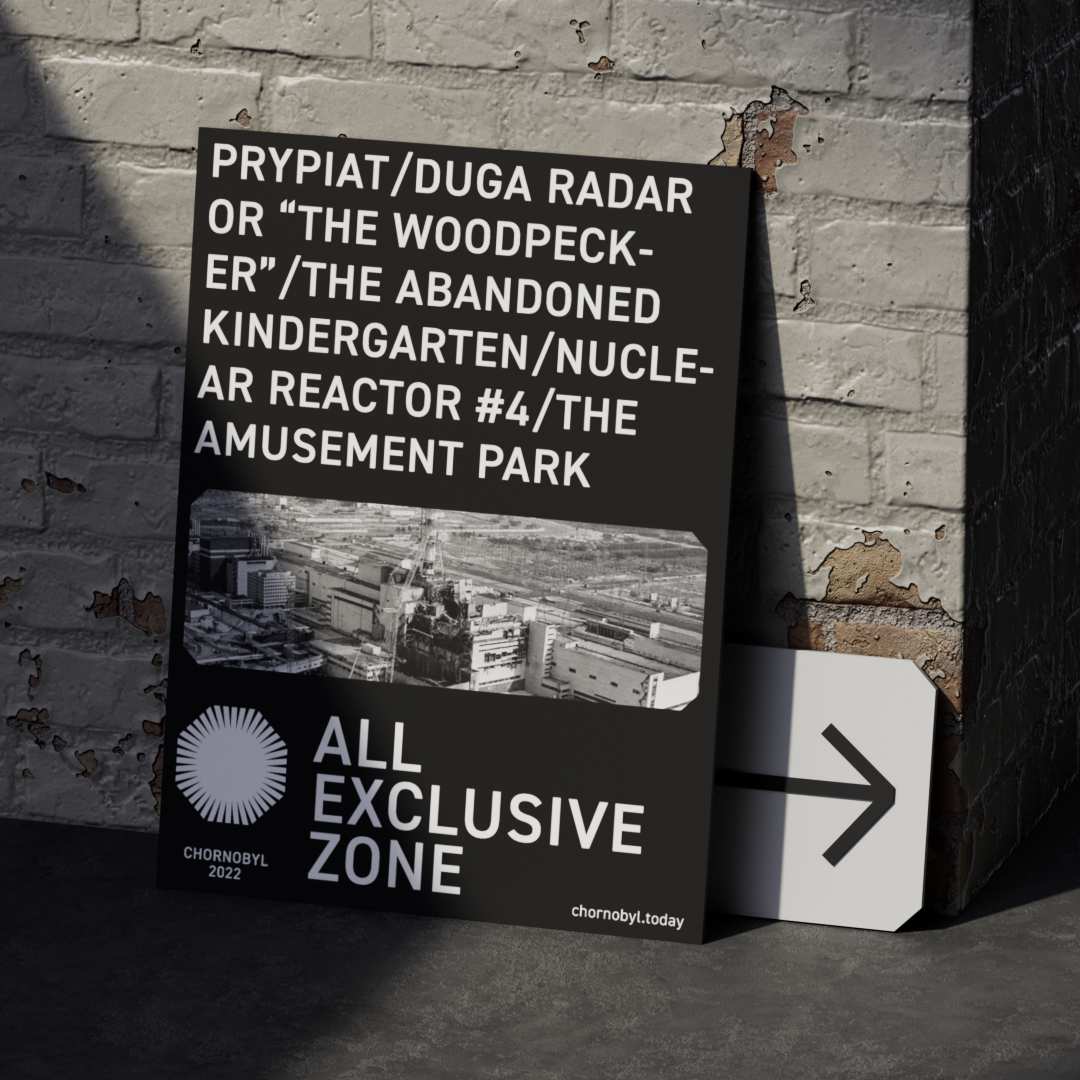

It was clear from the start that this would not be a typical branding project. There was no way to start by highlighting the pleasant aspects, tourist attractions, landmarks or “unique values” the place represents. After all, you won’t find any of that near the sarcophagus over the destroyed reactor!

So-called “disaster tourism” has reached Chornobyl, with the exclusion zone now attracting fans from all over the world. The designers aimed to present Chornobyl to those who had never considered visiting.

Source: Banda Agency

Source: Banda AgencyThey focused on two themes, two “disappearances”. First, the danger is gone. As Oleksandra explained, today, you get the same dose of radiation during a one-hour flight as you would if you spent 24 hours in the accessible parts of the exclusion zone. Secondly, the place itself is disappearing. Nature is reclaiming it, and in a decade, there may be little left to see. It’s a bit like a ghostly “atomic Venice”.

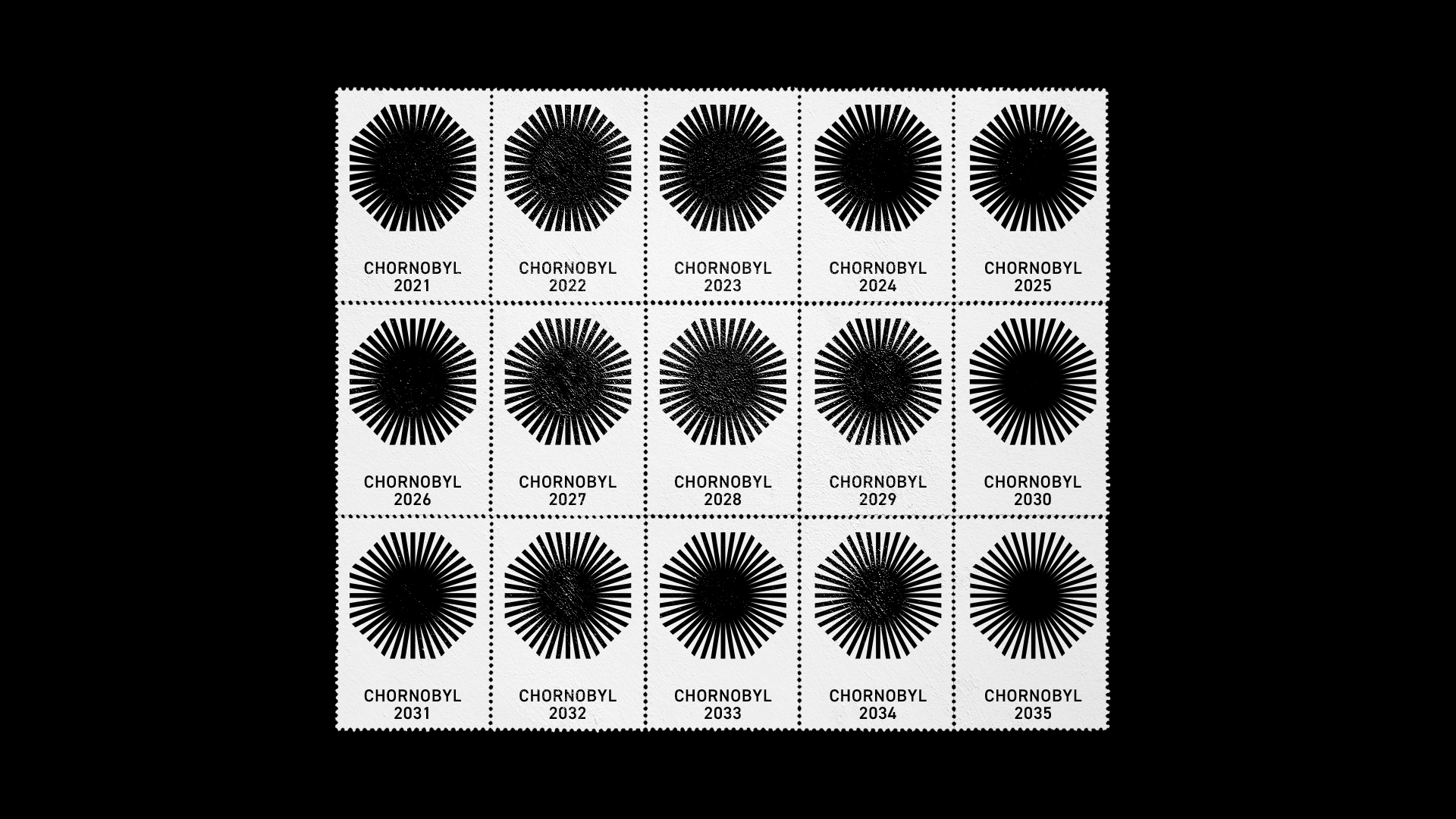

Knowing how ambitious and vital the project was, at the start of the process, every designer in the agency was invited to present their proposal. After a few weeks, when the concept was ready, a small team of strategists, two creative directors, two project managers and a single designer started work. This compact team faced a large decision-making committee on the client side. The client’s representatives usually numbered at least 15 people, with more appearing at each subsequent meeting – representatives from two ministries, the business sector, cultural experts and nuclear power plant employees. Summing up the year-long project, Oleksandra counted that Banda had given 27 presentations for their client!

Any branding project like this has to enter into a dialogue with the place’s past. Somehow it has to orient itself towards history. It can discuss it, ignore it or immerse itself in it. But how do you approach a catastrophe? Understandably, that is where Banda started. Fortunately, they managed to ensure that it didn’t overwhelm the project. Their design is not a mausoleum, a monument or a tomb.

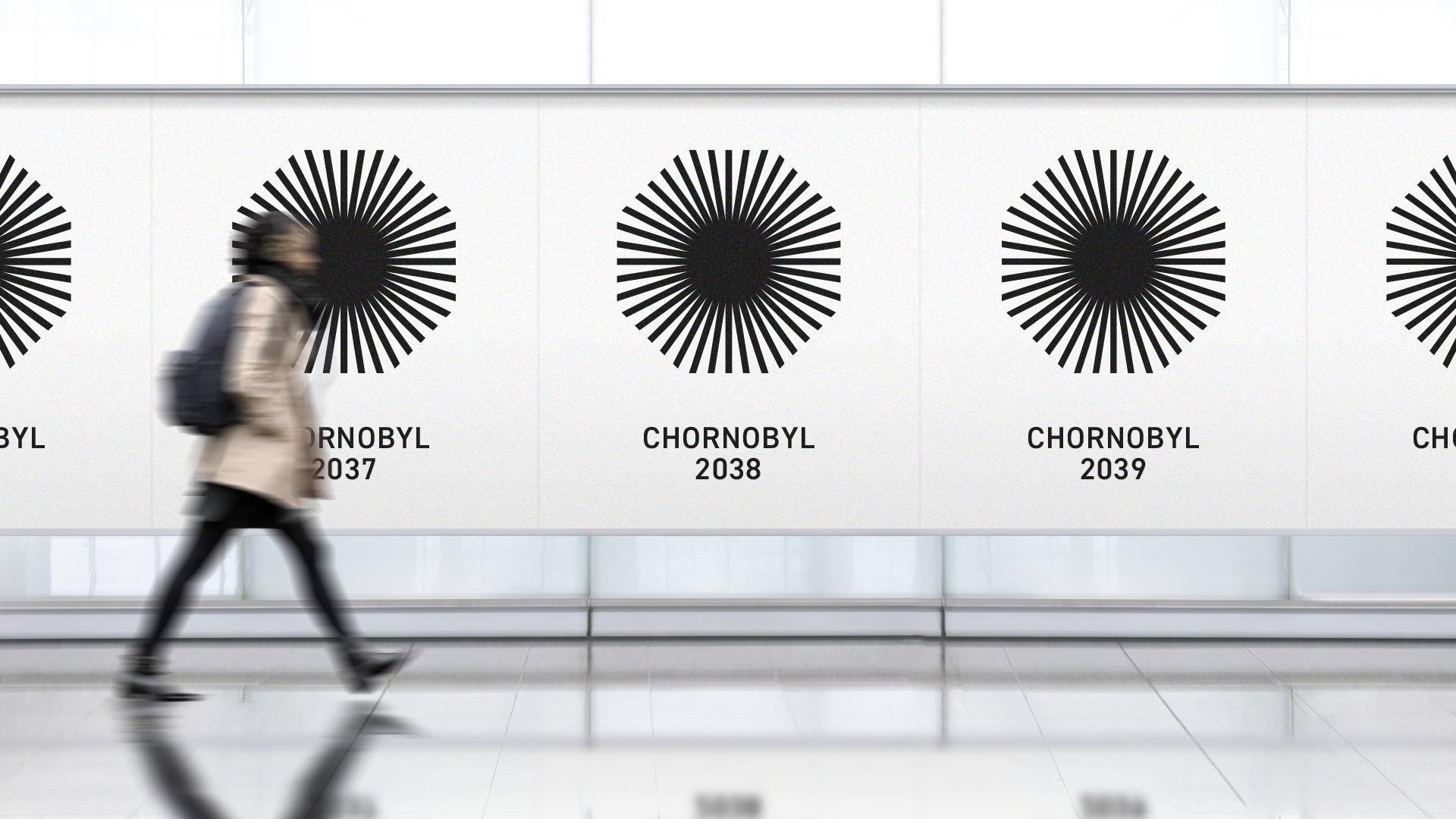

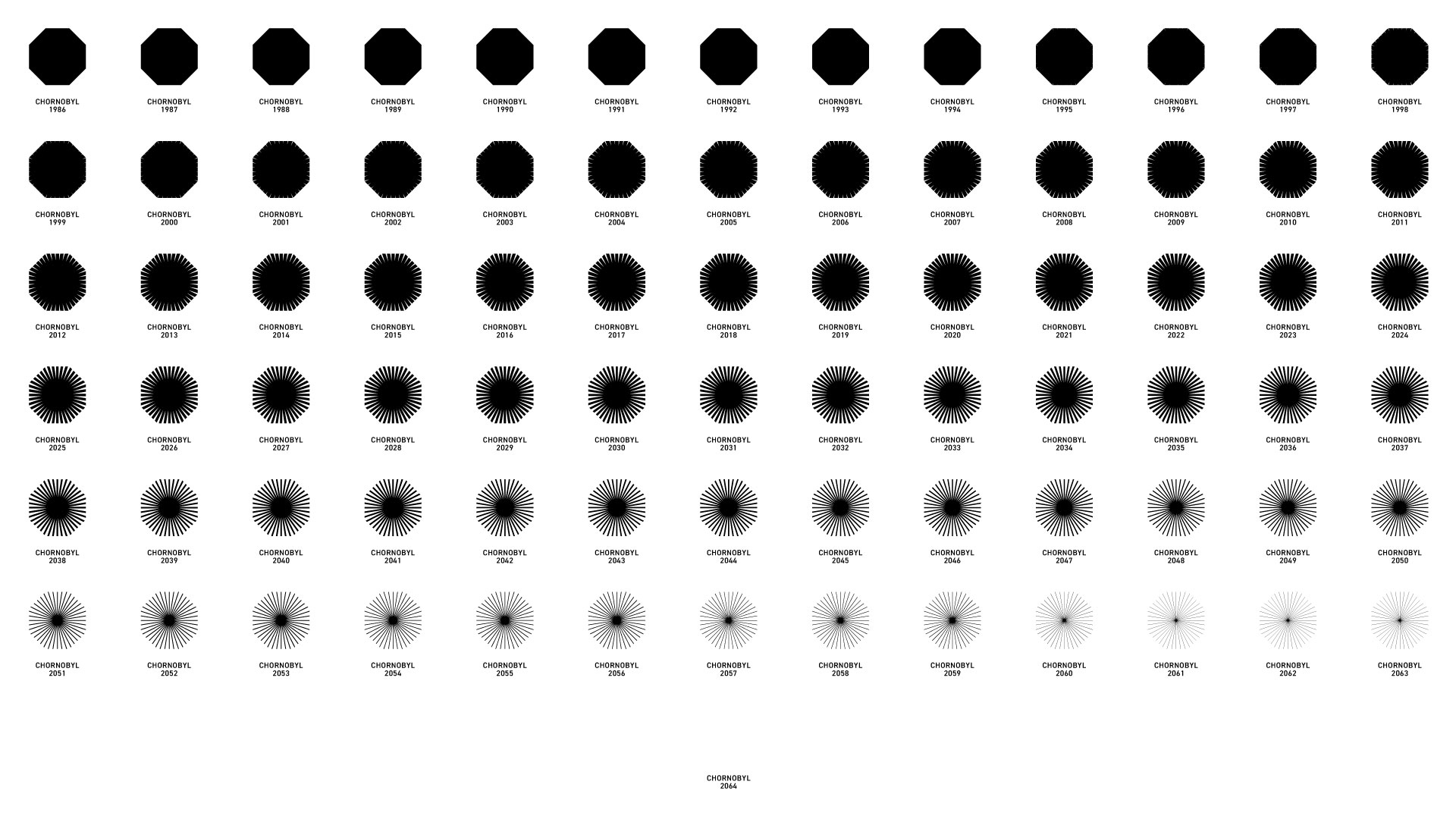

What makes this project unique is that time, and its inevitable passage are presented as the central and most significant element of the brand. “From the moment we realised that time would be our focus, I felt that the story of Chornobyl should be a box that we now fill with new meanings. The place changes and disappears every day. And while it may look familiar at first glance, inside, it’s different every time you look at it”. The brand mark designed by Banda – a simple black graphic symbol, straightforward typography and an absolute absence of colour – is intended to disappear by 2064, just as Chornobyl itself will gradually.

Source: Banda Agency

Source: Banda Agency Source: Banda Agency

Source: Banda AgencyAs Oleksandra says, “Colour was never an option. If you think of Chornobyl in yellow or green, it feels tacky and artificial, like we’re trying to cover up the tragedy of this place with fancy packaging to sell it”.

The graphic starting point for the logo is the shape of the fourth reactor, where it all began. This regular octagon was a challenge for the designers. It gave a sense of familiarity, and they had to work hard to ensure it was the right shape. Once that was settled, Banda created various branding materials, from wayfinding concepts, website and social media elements to T-shirts and hoodies.

Shortly after the project was launched on 26 April 2021, the anniversary of the tragic disaster, it received widespread attention and a positive reception both in Ukraine and around the world. Oleksandra remembers the excitement and the feeling that this place might finally have a future.

On 24 February 2022, Russia launched a full-scale attack on Ukraine, also reaching Chornobyl. For over a month, Russian troops were stationed in the Red Forest – the most contaminated area around the plant – while the plant’s staff were detained. “After what happened in the exclusion zone 2.5 years ago, I don’t think anyone is interested in reviving this brand. Considering the way the Russian army behaved during the occupation of the zone, it’s a miracle that there hasn’t been another disaster”.

A few weeks after the all-out war broke out, Oleksandra moved to Slovenia, where she still lives. Her priority was to ensure the safety of her daughter, who was not yet two years old in February 2022. As she puts it, her sense of time has stopped. “I live in constant waiting for the end of this unimaginable nightmare. (…) I’ve gone into ‘survive the day’ mode, with absolutely no plans for my life”.